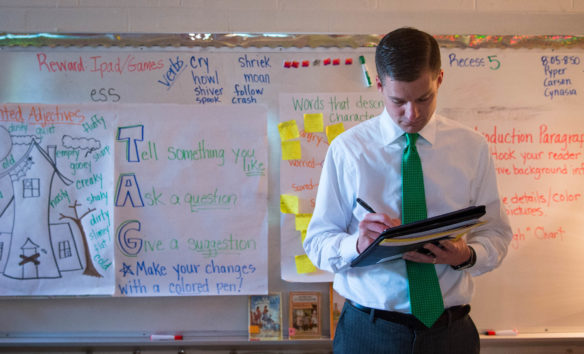

Photo by Bobby Ellis, Nov. 2, 2016

By Brenna R. Kelly

Brenna.kelly@education.ky.gov

Carrie Skirvin is reading a book to her kindergarten students when a little boy calls out. He doesn’t understand one of the words.

But he’s not in trouble for interrupting, he’s following directions.

Before she began reading, Skirvin asked students to alert her to any words they didn’t know – or as she calls them, interesting words.

“We’ll talk about what it means and that way we can understand what we’re reading,” she said.

On the next page, it’s Skirvin who finds an interesting word, podium.

“Look what Ms. Skirvin’s going to do, I’m going to code my thinking,” she said. “I’m going to make a connection, this is a text-to-self connection.”

She reminds the students about a podium they saw in the school, then asks them to close their eyes and picture someone standing at a podium.

Welcome to the Bellevue Classroom, a model of teaching and learning that Bellevue Independent created using tools from the Public Education and Business Coalition (PEBC), a Denver-based nonprofit that provides teacher training.

For the past two years, teachers and administrators at the 700-student district in Campbell County have been transforming their instruction using four foundations – Thinking Strategies, classroom communities, workshop model lessons and student/teacher discourse about their learning

“It’s really about equipping students as opposed to filling students,” said Bellevue Superintendent Robb Smith. “It’s providing them with access to tools to be successful in whatever they choose. We want a graduate of Bellevue Independent schools to be a competent, contributing member of society, and that starts at the kindergarten level.”

Teachers and administrators from across northern Kentucky have been flocking to the district to see the PEBC methods in action. The Northern Kentucky Cooperative for Educational Services has brought 10 districts to the school so far this year in hopes of spreading the practices across the region, said Amy Razor, NKCES executive director.

“We want all students in northern Kentucky to have instruction that focuses on analysis, comprehension and connections to build deep understanding,” Razor said. “Thinking strategies is not a ‘thing;’ but a mindset and a framework that will grow students. It’s not just a tool for the classroom, but a foundation to build robust life skills that will open the door for opportunities to all of our students.”

Smith, who is in his third year as superintendent, used the PEBC’s strategies during his time as principal at North Oldham Middle School and thought they would be a good fit for Bellevue.

About a fourth of Bellevue’s teachers have been to PEBC’s Thinking Strategies institute in Denver for a four-day training on the techniques. When they came back they shared what they learned, said Katrina Rechtin, instructional coach at Bellevue’s Grandview Elementary.

“It spread like fire; you can go in any room and you’ll see the same language,” she said. “We have some teachers that are better at certain parts of it, some have it all, but it’s really collaborative learning.”

The framework includes the seven Thinking Strategies, community, gradual release of responsibility in a workshop model and academic discourse. The framework gives students the tools to be metacognitive – to be able to think about how they are learning.

Photo by Bobby Ellis; Nov. 2, 2016

“Research shows that inclusion of metacognitive strategies as part of the schoolwide system for designing and delivering instruction positively impacts and accelerates student achievement,” said Juett Wells, the Kentucky Department of Education novice reduction coach. KDE encourages the use of thinking strategies as a best practice for closing the achievement gap and reducing the number of novice learners.

In the Bellevue Classroom, it all starts with the classroom community, Rechtin said. At the beginning of the year, teachers and students spend three to four weeks building their community – everything from choosing a class symbol to rules and procedures.

“It’s the whole group. It’s not the teacher anymore putting up rules and saying, ‘This is how we’re going to do it,’” she said. That way students take ownership and feel a shared purpose, she said.

“If you don’t have the community, it doesn’t work,” Rechtin said.

Once the community is place, teachers use the workshop model for lessons. Workshops include an opening, mini lesson, independent work time and then group reflection.

As the students work, the teacher talks to targeted students and formatively assesses their learning.

“You find out how each kid thinks, it’s not just what they know. You really know if they are understanding,” she said. “It’s just a totally different way of teaching.”

Teachers also use the seven Thinking Strategies to help students take ownership of their learning. The strategies give the students the tools that can be applied to any content.

To improve reading comprehension and vocabulary, students start out with their schema – a list of things they already know. Then as they come across new words, they use one of several strategies to figure out its meaning. Students can put the word on a sticky note, ask a friend, sound it out or look at the illustration.

When they work independently, students choose what the books the read or what they want to write about.

Students also annotate or “code their thinking” to help them make a text meaningful to them. The connection could be to something they know, another book they read or something in the world.

After the workshop session, students talk about what they learned. That could mean talking to other students, debating, writing or presenting to the class.

Bellevue started using the methods for reading and writing but will expand the concept to all content areas, Rechtin said.

“Content means nothing until a student activates his or her skills and does something creative or profound,” Smith said. “That’s learning.”

Several Boone County teachers and administrators got to see the methods in action during a recent visit to Grandview. As she watched Skirvin interact with her class, Alison Teegarden, an instructional coach at North Pointe Elementary, took notes on how Skirvin spoke to her students.

“I was really paying attention to how she was prompting them to think and how they were responding, and the thinking that they were doing out loud,” she said. Teegarden is hoping to introduce some of the methods at her school.

Teegarden said she was impressed by how Skirvin interacted with the students by being very intentional about what she says and how she prompts the students to respond to her.

“She is honoring their thinking. You can tell that she’s building that community to show them that their thinking is just as important as hers, which is really awesome,” she said.

That’s the key to it all, Skirvin said, making students feel in control of their learning.

“To be able to give them choice in what books they read and what they write about, it keeps them interested from beginning to end,” she said.

Attending the institute after more than 17 years of teaching was game-changing, Skirvin said.

“The last year and a half has been like going back to school and starting all over,” she said. “It’s totally different because it’s not all about me. It’s not me in charge; it’s us working together to learn as a community.”

There are a few challenges, she said. Now that her lessons follow her students’ interests, she can’t plan quite as far ahead as she would like.

“I go home every night and it’s, ‘OK, what did I do today and how am I going to do it tomorrow?’” Skirvin said. “Every day depends on the day before.”

But the results she see in her students are worth it, she said.

“Their writing is amazing,” Skirvin said. “If this is going to get them to become better writers or better readers, then I’m going to do that all year long. It’s all about student choice.”

MORE INFO …

Robb Smith Robb.Smith@Bellevue.kyschools.us

Katrina Rechtin Katrina.Rechtin@Bellevue.kyschools.us

Carrie Skirvin Carrie.Skirvin@Bellevue.kyschools.us

Amy Razor Amy.Razor@NKCES.org

Alison Teegarden Alison.Teegarden@Boone.kyschools.us